She was talking to me and I was listening, but I was also thinking about that moment in My Best Friend’s Wedding when Julia Robert’s character should have told Dylan McDermott’s character that she was in love with him, but she didn’t. “You know that other thing that you mentioned? I’m that too”, I said. This is how I came out to my Mom, in the middle of the hallway, jacket in hand, ready to pick up ice cream from Coldstone’s. Three hours earlier I had confessed to my über Christian Mother that I had my doubts about the father, the son, and the holy ghost. “Your Grandmother would be rolling in her grave”, she said. “Well, I don’t believe she’s there”, I replied, avoiding contact with the two half moons that are her eyes. I wish she was here, now, I thought. Grandmother knew that I was gay but she didn’t force me to admit it. All she said was, “If you don’t start bringing girls around, you know they’ll think you’re funny.” Cue awkward silence. We gazed at 1999’s September setting sun. She sat in her chair on the porch, while I rested at her feet. “Well, if you are funny it’s okay with me. You’ll always have a home.” She should have been the first person I told. Maybe things would have been different had I said right then and there, “Grandmother as soon as I recognised I was a conscious being, I was aware of my ‘humour’. I am so funny I think I might be a comedian”. Like all powerful matriarchs, she would have made them accept me. It was too late to think such thoughts because she died five years before my clumsy confession. We were all alone that day, just me, Mom, and the truth that I meant to tell her. “I don’t believe in a loving, all powerful deity that needs us to worship it. I don’t believe in free will that results in punishment for disobedience.” There, I’d said it! She looked like she was going to implode, disappearing into the tears that sled down her cheeks. “This is the worse thing you could have ever told me. I thought you were going to tell me that you’re gay.” If I didn’t tell her then, I knew I would never tell her. When the deed was done her first words were, “But you’re Black. Your life is already difficult enough”. Sometimes I take myself back to that moment in the hallway, and I stand just to the left of the two people having this conversation. Those people, that Mother and that son don’t exist anymore. If I had it all to do again, I wouldn’t change a thing. When I think about my Mother’s initial reaction, and I replay the words, “But you’re Black”, I sometimes wonder with a smile, Did she curse me, or did she simply know what was waiting for me? Growing up she told me that one day something would separate us. The truth can do that sometimes.

“Equality scream the White gays, with legalise gay across their shirts and no Blacks no Asian and no Fems across their Grindr profiles.” These words were part of a post shared by one of my Facebook friend’s who we’ll call It Boy, because he was a part of a crew called The It Boys. In Berlin’s gay/queer scene I found myself dealing with racism on a regular basis. It was refreshing to see It Boy’s post, until I spotted the very first comment directly below it. “Like a Black guy never wrote No Asians No Fems on their Grindr profile or vice versa. Isn’t the point that discrimination sucks regardless who it’s coming from”, wrote Not-His-Real-Name Bucky. No. The goal of this post is to highlight White men who advocate for gay rights while simultaneously engaging in racial discrimination and femphobia. Bucky and I went back and forth and up and down on the blue and white screen from 14:00 til well after midnight. “Why can’t we discuss racial discrimination as practised by White men in the gay community? Why are you bringing up femphobia and anti-Asian sexual racism performed by gay Black men? You’re deflecting from the issue.” It Boy and a member of his crew jumped in adding insightful comments and testimonies. “Bucky is everything but a racist. He has friends in all colors and shapes”, It Boy certified! “It isn’t only about race. POC men can be sexist when they deny femmes for some joyful play.” That was Not-His-Real-Name Sandy. He had a lot of comments! This all happened on March 25th, 2015. Looking at this Facebook conversation now, I realise that these gay men weren’t really interested in having a discussion about racial discrimination in the gay community. Bucky felt like the message of this post was harmful, and even hateful. Sandy felt like my criticism of Bucky’s post privileged a discussion about race over femphobia, and for him this immediately and automatically devalued what he agreed could have been valid points. One of the last things Bucky communicated before dropping out of the conversation was that I was being unfair, just as It Boy’s post had been unfair in its generalisation of White men. Bucky is ignorant. He doesn’t understand that White men, White women, gay White men, and gay White women have something that I’ll never have when confronted with stereotypes and generalisations based on race. What is this superpower? It’s called objectivity. Let’s look at how this works.

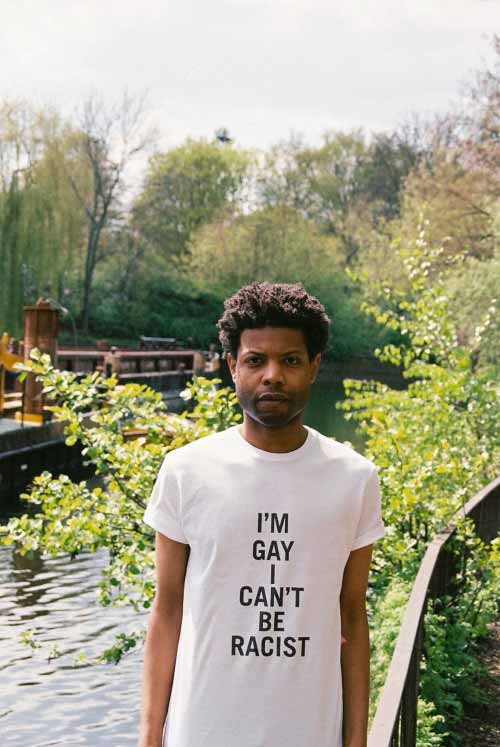

“You didn’t have any of the songs I wanted to hear. Grace Jones is my favorite. I’m so mad that you don’t have her music. How can you not have it? You should have Grace Jones because you’re Black.” Every Sunday, I dj-ed at one of my favorite bars for free drinks and enough money to pay, at the very least, my rent. Customers were always asking me to deviate from my Indie rock, Electropop sets. What they didn’t understand was that I was not allowed to play what many of them referred to as ‘Black music’, because the management felt that this kind of music made the customers too aggressive. Insert subtext here. Once I was asked, “Why doesn’t a Black guy play Black music”? A loyal customer overheard the calamity. Winking at me and then turning to address my inquisitor she said, “He’ll play some Nigger music later, just sit down and relax”. The Inquisitor and I shared a moment of recognition. A moment of recognition occurs when you find yourself arriving at similar conclusions with one or more persons engaged in conversation. The Inquisitor and I were stumped, but for different reasons. You know how racism can leave you speechless at times? Yeah, that was one of those times. There are other times, other moments where I know exactly what to say. Moments where I don’t have Grace Jones, and I don’t feel like dealing with racism gracefully. He had pulled up to my bumper, and I wasn’t having any of it. “The idea that I should have, do, or be anything based on the color of my skin is racist”, I said behind clenched teeth, trying to keep my composure. He backed away and threw himself on an available bar stool. “Don’t call me racist”, he shouted, “I’m gay”! Why do they always make it about them? Not appearing racist is more important to them than making sure that they don’t reproduce racism. He, apparently wasn’t finished. Cocking his head towards me, arms akimbo, he barked, “I can’t be racist I’m gay”. For him it was as simple as that.

I’m gay I can’t be racist. This idea, this statement, implies so many things all at once. A White person who believes that being gay excludes them from replicating racial oppression doesn’t understand the difference between race and sexuality. This ignorance is deleterious, negating the experiences of people like myself: non-White people who are gay, and are subjected to racism, homophobia, and incomparable forms of oppression found in the spaces where sexuality and race intersect. This gross misconception completely bypasses Whiteness as an integral part of this equation. If this delusion could talk it would say things like, “Me, racist? Never that! How can I oppress you when I am privy to homophobia. I know what it’s like to be marginalised and my suffering isn’t any different to yours”. This fallacy might also claim that all forms of oppression operate in the same manner, producing similar outcomes. Suffering is therefore, not subjective, and forms of oppression do not vary under different circumstances from person to person. You’re probably well acquainted with these erroneous ideas, which might, if featured on a poster, present a group of individuals who are not cis-gendered, straight, white men, in a canoe somewhere in the middle of the ocean, united against a current that could swallow them whole if it chose to. “I’m gay, I can’t be racist”, sits comfortably in this canoe, alluding to an inherent sense of solidarity between marginalised people. If this was a fixed and finite fact, we might live in a very different world, perhaps a world without ‘isms’ and ‘obias’. If facing prejudice and discrimination as a White gay man prohibits an individual from harbouring racial biases and engaging in the racial oppression of non-Whites, what other forms of oppression are gay White men incapable of reproducing and are there forms of oppression that Black people cannot impose because we are privy to anti-Black racism? To be fair, that word which implies that we live in a meritocracy where everyone has the same rights, the same privileges, and the same opportunities, I propose we conduct an experiment right here, right now.

I’m gay, I can’t be Islamophobic. I’m gay I can’t body shame other men. I’m gay I can’t be an ableist. I’m gay I can’t be xenophobic. How do you feel after reading these comments? These remarks sound funny don’t they? Do you know why that is? We are aware that the speaker in this exercise is White, and we know that White people, gay or straight, are automatically afforded objectivity. That word again! Objectivity is the reason why the videos that we sometimes share which place White people on the other side of situations that non-Whites often find or lose themselves in are laughable, but in the end unsatisfying. We as non-Whites can stereotype White people, but these stereotypes don’t seem to stick the way that stereotypes involving people of color fix themselves to our bodies , recirculating within the framework of the dominant culture as we travel through our lives. Let’s look at Blackness to see if there’s anything that it can’t do! I’m Black I can’t be sexist. I’m Black I can’t be anti-Semitic. I’m Black I can’t be homophobic. I’m Black I can’t be transphobic. How do you feel now? Does your stomach hurt a little?

There’s a big, very clear difference between these declarations, and at the root of this disparity is power. While I recognise that the “I’m gay I can’t be… statements” are funny because I’ve been taught by every agent of socialisation that the oversights, dubious behaviors, indiscretions, and heinous offences committed by one White person cannot possibly reflect millions of other people who happen to be White, I have witnessed gay White men body shame both men and women, I have heard gay White men make Islamophobic comments, and I have challenged expressions of xenophobia presented to me by gay White men. I’ve also witnessed gay White men performing sexism, femphobia, and transphobia. When we read the “I’m Black I can’t be…” affirmations we can’t laugh, because every agent of socialisation tells us exactly what Black people can and cannot do, diffusing this data into the fabric of a collective consciousness. A White person’s experience with one or more Black individuals can function as a map, or a guide book which explains what to expect when in the company of other Black people. Do you remember the viral video sensation 10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman which featured a young, White heroine walking through the city’s streets while being harassed by a cast of non-White men? Were you less than surprised when it was revealed that Bayna-Lehkiem El-Amin, who was nearly charged for a homophobic hate crime, turned out to be gay himself? “Did you, sans shock and awe shout, “Twist”, only to read months later that El-Amin would serve twelve years for a fight that he didn’t start? If it’s necessary for Black people to reject conventions of race so that we can fully see ourselves and our humanity, what work awaits White people when they realise that the benefits of being White are a given because so much has and continues to be taken from people of color?

When I look at Peggy McIntosh’s list of White privileges, many of these privileges are extended to men and women who happen to be White and gay: I can be casual about whether or not to listen to another person’s voice in a group in which s/he is the only member of his/her race. I can be pretty sure of having my voice heard in a group in which I am the only member of my race. My culture gives me little fear about ignoring the perspectives and powers of people of other races. I can arrange my activities so that I will never have to experience feelings of rejection owing to my race. I can turn on the television or open the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented. I can be sure that if I need legal or medical help, my race will not work against me. If I declare there is a racial issue at hand, or there isn’t a racial issue at hand, my race will lend me more credibility for either position than a person of color will have. I can go home from most meetings of organizations I belong to feeling somewhat tied in, rather than isolated, out-of-place, outnumbered, unheard, held at a distance, or feared.

There are fifty privileges mentioned on this list. The privileges I’ve shared here are just some of the benefits that White gay men have access to. The freedoms listed here are not guarantees that I can redeem when I open a gay magazine, visit a gay clinic, party in a gay club, work for a gay organisation, or make my home in a gay flat share. What are some of the White privileges that you’ve observed White gay men taking advantage of? Here are a few that come to mind: When speaking about homophobia I can choose not to focus on homophobic acts of violence or open displays of discrimination based on sexual orientation perpetrated by people of my race. I can see these acts as isolated incidences. When individuals who are not of my race exhibit homophobic behavior, I can compile these experiences together and can publicly discriminate against these racial groups, labelling anyone belonging to these groups as a potential threat to my safety. If I am questioned about my sexuality when in the company of gay/queer individuals, this scrutiny will have nothing to do with my race. In general I never have to worry about being rejected online or in real life by potential romantic or sexual partners based on race. I can compare my struggles as a person who falls under the LGBTQ spectrum with racial oppression while remaining silent about the suffering of people exposed to racism. I can openly exhibit racial prejudice in gay/queer spaces and can defend myself during confrontations by saying, “I’m gay I can’t be racist”. Sometimes I have the impression that the only valid observations that a Black person can make about race, are comments which deny the existence of racism flat out or diminish the effects that anti-Black racism has on our lives. What do you think? I want to know.

Isaiah Lopaz, Him Noir.

message me at therealhimnoir.com