Isaiah Lopaz is a black American living in Berlin. On a regular basis Germans ask him where he comes from. No, no, where he really comes from. He’s a college-educated artist and writer — who is frequently mistaken for a drug dealer.

The influx of more than a million migrants into Germany the past two years has forced the country to wrestle with issues of race, ethnicity and identity. Mr. Lopaz says that he feels that Berlin is home, but also that the issues the migrants face have been a part of his world since he moved to Germany nearly a decade ago.

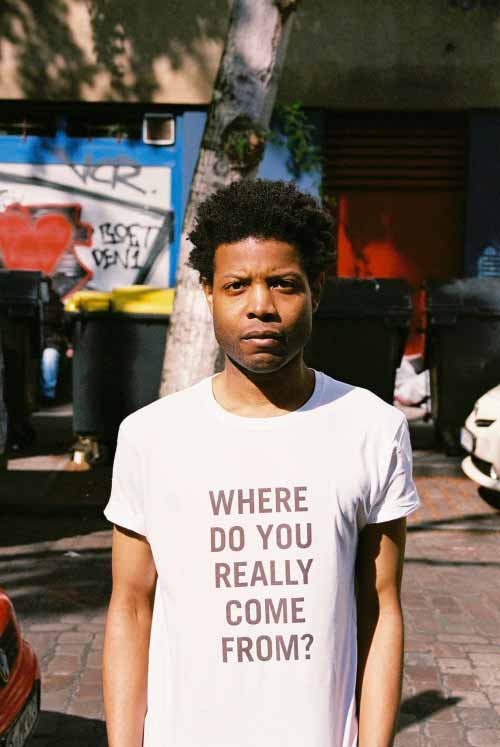

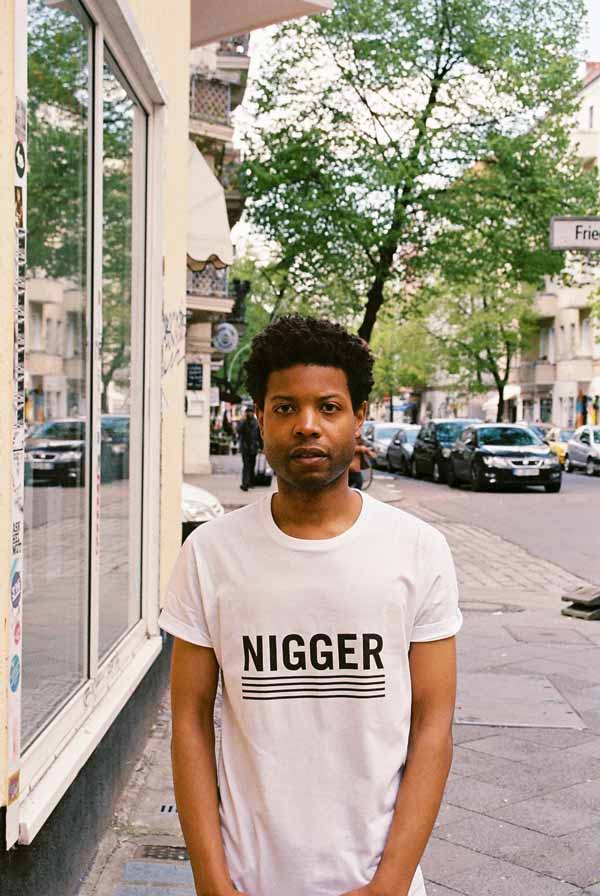

Mr. Lopaz, 36, found a creative way to address instances of racism: He took the offending comments and put them on T-shirts. He then directed a series of portraits taken by his best friend, Richard Hancock, around Berlin. I talked to Mr. Lopaz multiple times about the stories behind some of his T-shirts. His comments have been edited.

Mr. Lopaz, who speaks conversational German, used to have dreadlocks, and nearly every time he went out, he was approached for drugs. He would be at a bar or an art opening, and friends of acquaintances would ask him if he had drugs. In the summer of 2007, soon after he moved to Berlin, two people followed him around a grocery store before approaching him.

At some point I just cut my hair. I cut it for lots of reasons, but I also knew that if I cut my hair I bet this is going to go away. The truth is that it didn’t go away completely, but the frequency of people coming up to me and asking me for drugs, it lessened.

A lot of people that were really close to me felt really sad. They were like, “Oh, but your hair was so beautiful.”

Yes, I was dealing with people asking me for drugs, but there were lots of other more invasive forms of racism. To cut my hair and have one less thing, it actually was a big blessing for me.

At least once a day I will make eye contact with a white man or white woman, and they will grab their belongings as they notice me. There is this idea that black people are not to be trusted, that black people are criminals, thieves, deviant. We don’t have these ideas about white people. We as black people don’t have objectivity. We are judged based on stereotypes.

Mr. Lopaz’s maternal and paternal grandparents were part of a wave of black Americans who left the South for other parts of the United States in the first half of the 20th century. His parents grew up on the same street in South Central Los Angeles, and he was born and raised there.

It was very strange for me to be asked over and over, “Where are you really from?” They want me to say that I am from Africa. There are several reasons that I cannot really give them this story. One reason is that I am not from Africa. But also, there is a lot of pain that comes with this. It is painful because we were never meant to know where we were from.

I also come from a very multicultural family: Three of my grandparents were half Native American. Some of my ancestors built America, and my other ancestors were there before colonization.

Of course I have ancestors from Africa, but I think this question denies the impact and the culture that we as black Americans have created.

In 2011, Mr. Lopaz met two German women at a bar in Berlin. One of them, the director of a preschool, began quizzing him about where he was from and arguing that the United States had not been a country long enough to have its own culture. Then she told him, “And you have no culture because you come from slaves.”

That is the worst thing that anyone has ever said to me in terms of race.

As a black person, I don’t represent for most Germans somebody who can be a part of their society. There is a resistance to welcoming black foreigners but also to making black citizens feel comfortable.

I can pass the citizenship test, I can become a citizen, I can receive a passport, I can speak German fluently, but I don’t see myself ever being accepted as a German.

I do feel like I have met my best friends here. This is my city. I have a name here. I have a place here. But I don’t see myself staying here long term because I want a little bit more. In other cities, I can be another face in a crowd.

Mr. Lopaz, who is gay, has had a number of part-time jobs working in the gay night life scene in Berlin. He has also exhibited his work in galleries owned or run by gay Germans.

I think that what keeps other gay people from recognizing my sexuality is the fact that I am black. I find that very strange; it’s something that only happens in Germany.

It happens when I go to a gay club, and they say, “You know this is for gay people, right?” Or I’m chatting with a guy at a bar — at some point, he says, “Oh, you’re gay?”

There are several gay events where they will not play hip-hop music featuring black men. As one promoter said, “The men are too sexist and too aggressive.” How can they make such a blanket statement about hip-hop? I think it’s very strange and racist to say that because some people are sexist and homophobic, all of the artists are. It’s really problematic.

There isn’t space for my blackness. I often have to deal with microaggressions. I often have to deal with racism. I end up not going to these queer, gay spaces anymore.

Mr. Lopaz worked as a D.J. at a gay bar in Berlin for two years and often heard racist remarks from customers. One night a man was angry that Mr. Lopaz didn’t have music by the singer Grace Jones and told him, “You should have it because you’re black.” The argument escalated, and Mr. Lopaz complained to his supervisor. But the supervisor was not sympathetic — instead, he told him that racism against blacks didn’t really exist.

I shut off my computer, which is how I was D.J.-ing, and I left the bar. I grabbed my things, slammed the keys on the counter. I knew that if someone had said something homophobic to me, they wouldn’t have put up with it. I was tired after having worked there for two years having nobody do anything about it.

I was fired from the job for being unprofessional. I cannot always be this “good black person.” That’s just not realistic. And I don’t want to be that. I don’t encourage my friends to be this. I wouldn’t teach my children to be this way. You deserve to be treated well, and you deserve to have rights.

A white German who also worked at the bar later argued with Mr. Lopaz over the incident. Mr. Lopaz’s colleague told him that he, too, had faced hardship when called a “Nazi.”

He said, “Black people are always talking about racism. Jews are always talking about anti-Semitism. There are lots of other people who are having problems, too.”

And then he said: “The N-word isn’t the only bad word. The N-word is the same as a Nazi.”

I am sorry that people are calling you that, but it’s not the same. It’s not a word that has been used to oppress white Germans.

More: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/17/world/europe/berlin-racism-isaiah-lopaz.html