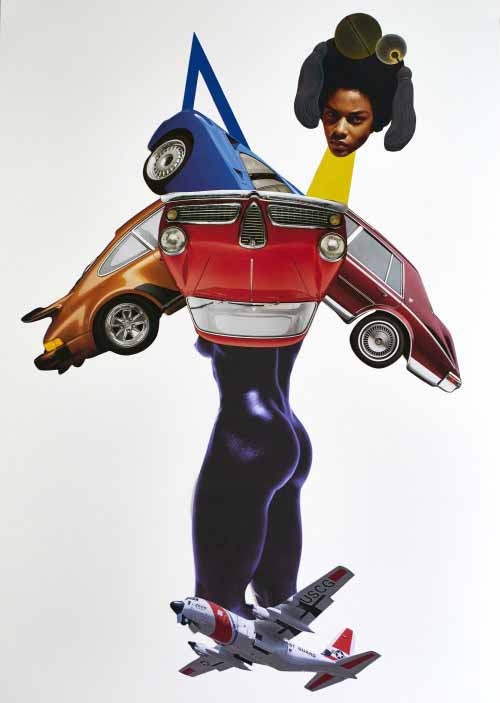

Untitled Transformers II, Collage On Bristol Board, 2016 by Isaiah Lopaz

Transcript from Acceptable And Inconvenient Narratives Presented

At The Schwules Museum on May 19th, 2016

Mythology has always been a very important part of my life, and for good reason. I was surrounded by fantastic people growing up, big personalities with even taller tales. My first ‘shero’ was my Grandmother. Her laughter was like thunder. Her love was a never ending fortress where I felt inspired and protected. Her anger was like a thousand arrows that hit every target that they were aimed at simultaneously. I would stare at her face and try to remove the lines that time and trouble had chiseled onto her beautiful visage. Mrs. Robinson (as she was known for most of her life) was 5’ll, about as wide as she was tall, hawk eyed, sharp tongued, and a force to be reckoned with. My chain smoking, shotgun wielding, Texan Grandmother narrated the misadventures of her life between passages of Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John, and I accepted every detail like the bread and wine we had every Sunday for communion. “Do you know why I left Texas”, she would ask with her buttery drawl? All of my Grandparents were part of a great migration of Black Americans who left the American South for the American West in search of freedom, adventure, and more autonomy. As my Grandaddy said, “Less racism”. This is why I try to smile politely when people tell me that they think that Los Angeles is fake and that they have no interest in going there. Fair enough, but narratives about Los Angeles don’t tell this particular story, the histories of people that I come from are absent. My Grandparents left their friends, their families, their cultures, essentially all that they had known because they did not have the opportunities to be the people that they wanted to be. They had no interest in fame or fortune, although my Grandmother did turn up to parent/teacher meetings in fur coats, pearls, and heels. When I hear other people speak of the African diaspora, I wonder if there are parallels or moments of recognition between those who left Africa for other countries, and those who left the American South for the North or the West?

“I had to leave Texas little man. Here’s what happened. Your Great Grandmother was a mean, mean woman. She hated me because I reminded her of my Dad, who she loved, but who left her for another woman. We lived on welfare. We would receive the most beautiful clothes from the government, but the clothes had a patch on the front that read welfare. Imagine the most beautiful clothes you can think of with the words “WELFARE” written on them. Your Great Grandmother was Indian, from Arkansas. She gave me away to Miss Sarah, but I wasn’t sad about it. Miss Sara loved me like her own daughter and taught me about the good Lord. Mama took me back years later, I think just to spite me. She couldn’t stand the idea of me being happy or taken care of. Well I got pregnant at age 17. My boyfriend at the time came from a wealthy Black family in Belton, but he didn’t want to have anything to do with me. His Mother, however, was interested in the child, and she told me not to hesitate to contact her if I needed anything. I had a baby girl. I named her Constance. She was my everything. One day she caught a really bad cold. I didn’t have enough money to take her to the hospital, so I went to see her Grandmother, Mrs. Rich Black Belton. Well, Mrs. agreed without hesitation to help me. She told me to come to her house the next day and that she would sort everything out. I was so happy Little man. I was so happy! I came back the next day with Constance and there was a car waiting to take us to the hospital. Mrs. asked me to come in for a glass of cold water, said she had some hospital papers for me to sign. Sure, Sure, anything I said, I was so happy that Constance was going to get some help. Well, I signed the papers without even reading them and we took Constance to the hospital that day. She got better and better. I went to the hospital on the day she was to be discharged and I saw Mrs. holding her in her arms. She was surrounded by Doctors and a very stern looking man. I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what it was that was wrong. I went up to Mrs. with my arms out stretched for my baby, for Constance and Mrs. turned away from me. I wanna take her home. She’s well now, aint she? Mr. Stern came forward with papers in hand. You won’t be taking her home girl. You gave away that right when you signed these papers. I felt sick, like I was about to vomit, and out of my mouth, my soul would fall, out onto the floor. I hadn’t read the papers and Mrs. had counted on that. I screamed, hollered, and lunged for my baby, but they were all against me and I was all alone.

I wasn’t allowed to see her. Her father was gone, and wouldn’t have done anything to help me. Wouldn’t have tried to talk some sense to his Mammy. The thing that always bothered me was that he didn’t care nothing about Constance. Nothing at all. I was powerless. No one could help me because legally, Constance was “hers”. About three or four years later I met and married a new man. I asked him to help me get my little girl, so that we could take her away and that’s when we began to plot. She had a nanny who took her to a park. A friend of mine had told me that she saw her there. The nanny didn’t know nothing about me, so I went to the park and played with Constance and talked to her nanny. I told the nanny that me and my new husband were expecting a baby and that I loved children. Constance took to me. She just took to me. On the day that we planned to kidnap her, my Husband distracted the Nanny while I was way across the park with Constance. Constance knew that she had a Mother, but she didn’t know that it was me! I revealed to her who I was and asked her if she wanted to live with me. She believed me, believed that I was her Mother and said that she wanted to come with me. My husband and I had planned to leave that very day to California by train. In a flurry I took Constance to the train station. I never ran so fast in my life. When I got to the platform I looked everywhere for my husband. He had told me that he would do what needed to be done to make sure that he could meet Constance and I at the train station. In the distance I saw the train coming, but I didn’t see him. I didn’t see him anywhere. I turned around and down the platform I saw police. I knew straight away who they were coming for. There was nowhere for me to go. They tore Constance out of my arms and took me downstairs and there was Mrs. waiting for me with the nanny and more police officers. Constance ran to Mrs., who scooped her up in her arms. “They want to put you in jail, and I ought to let them, but if you leave Texas and promise to never come back, and to never contact Constance I won’t let them do it.“ So I left. I came to California. I worked in a glass factory until I couldn’t stand the manager’s advances anymore, I made and sold homemade peach brandy, and did odd jobs. I left and I didn’t go back to Texas until Mrs. had died, and when I went back there was nothing waiting for me there”.

Having heard this story several times over, even at such a young age I understood why her sorrow seemed to flood the whole house for days on end. I cried when she and my Mother argued because I knew that if Constance had been a constant, all of our lives would have been more peaceful. I was left alone with her for weeks at a time in our home on 104th street in South Central Los Angeles, a place where I witnessed her anger in many different incarnations. It could have burned the whole house down, but so powerful was she, that even in her anger she made a space for me where I could feel the warmth of the fire, but could not be consumed by it. We watched Wonderwoman, He-man, Buck Rogers, Transformers, The Smurfs, and Voltron together, and in my mind Velma Odessa Robinson, who was thought to be named after Odessa Texas, but was in truth named after Odysseus, was just as powerful as any demigod or extraterrestrial Moses who ever fell to earth from the heavens,or the planet Krypton.

At this time, I too wanted to be powerful. “I want to have powers”, I would say. Naturally my Mother and Father thought I was disturbed. Power to me, meant control over my own life, it meant freedom. The first time I contemplated myself, the first time I realised that I was alive, took place in my Grandmother’s home. I was just four years old, and I knew that ‘I was’, and that this experience was one that was in continuation. I longed to be able to express my full self, but I knew that there were parts of me that I couldn’t speak of, or express. I wanted to be like my Supersheros and Superheros. They always knew what was just, what was good, or what was right, and they never failed or struggled to perform good deeds. I had set a task for myself which I called “A day without sin”. A day without sin would be a day where everything that I did was right and acceptable, but this day would not count unless my thoughts were good, pure, and normal. I never managed a day without sin, and it was years before I gave up trying, before I realised that such an idea, such a mission, was a fool’s errand. I didn’t relate to Skeletor, Lex Luthor, Gargamel, or Darth Vader. I didn’t want power to control others, I didn’t need to be worshiped or admired. I needed to be complex, because that’s what I was, or how I felt at least.

I have connected with the idea that I am not so complex, but that I live in a world of acceptable and inconvenient narratives that define people like myself as complex. Acceptable narratives are rooted in power. These are the narratives that often go unquestioned. You learn these narratives in school, through print and online media, at church, on the street, at work, when you travel, and often when you interact with strangers. It is inconvenient to question these narratives for those who benefit from their structures, but for those of us who do not benefit from these structures, we have the ability to be who and what we really are because narration is a creation of the self, and questioning acceptable narratives will bring you home to your true self and your true power.. Inconvenient narratives are the truths that we find when we step away from the oppression of acceptable narratives.

When I’m at home making new collages or new paper cuts, I am almost always listening to podcasts, lectures, artist interviews, or documentaries. Recently I’ve had the “I too Am Harvard” documentary on repeat. In this documentary, young Black students who attend Harvard, one of America’s most prestigious universities, narrate what it means to be Black (to them), and what it means to be a Black student attending Harvard. There are two statements that stick with me. One student remarks that he, “Always questions knowledge. Not necessarily what we know, but how we know what we know in the first place.” Another student declares that “Blackness is faith in what you don’t see, because we as a people often don’t see ourselves. We don’t see uplifting images of ourselves.” When I was asked to exhibit work in the Schwules Museum’s cafe and to give a presentation here, I enthusiastically said yes, because how many times do you get to see a gay Black artist speak in a space such as this? A more urgent, important, or poignant question would be why is this so rare… but we know the answer to this question already. I was asked to speak about Black Superheroes, racism, and postcolonialism. The elephant missing from the room was the topic of racism in the gay community, an elephant that is often in Queer spaces that I inhabit here in Berlin. I don’t feed him peanuts, but he shows up, often to my dismay. If you are Black, LGBTQI, Queer, gay, and keeping your head above water, please allow me to salute you right now. You truly are a s/hero to me. Acceptable and inconvenient narratives intersect frequently in the journeys that are our life experiences, just like gender, race, and sexuality, criss crossing and swirling around the bodies that we inhabit.

Although we have much ground to cover, and I am aware that we have a limited amount of time, let’s look at comic books, sci/fi, and fantasy, because we can learn so much about the experiences of Black lives today. I always start with Rue from Hunger Games. Spoiler Alert ahoi! Rue is a young character from the Hunger Games’ young adult novel series who dies in the first book. When the film was released, many fans expressed outrage because Rue was portrayed on screen by a young, brown, curly haired Amandla Stenberg. One fan commented that “When I found out Rue was Black her death wasn’t as sad.” This sentence was followed with the words, “I hate myself”. Indeed one must hate one’s self to feel less sad about the death of a young child, real or imagined. For me there’s more gravity to this statement because we are talking about a fictional character. The apathy expressed here is often present when it comes to violence directed towards Black lives across the globe. Convenient narratives portray Black bodies in abject poverty, starving, or emaciated. Inconvenient narratives include the stories of countless Black women who have been shot and killed in America, or the Black Christian students shot in Kenya. These narratives don’t receive Facebook profile badges that suggest solidarity. Our tragedies are not on par with other tragedies. At the Golden Globes or Cannes Film festival celebrities don’t use white pieces of paper to highlight the loss of Black lives. When I reflect on this fan’s reaction to Rue’s death (there are many more horrible comments), I think, excuse me for swearing, ‘Damn! They don’t even want to imagine us in their fantasies’. Let’s talk about spaces where we see acceptable narratives, featuring Black bodies.

Jimmy Kimmel is the host of a popular prime time television show in America. The show features interviews with celebrities, skits, etc. This year the Jimmy Kimmel show did a skit regarding the Oscars So White controversy. For this particular skit, several Oscar nominated films were reimagined with Black characters. Room for example, became “Crib”. This skit utilised “slang” which some of us speak fluently, and made use of stereotypes to alter the story lines of these critically acclaimed films. Most of the criticism surrounding the skit focused on the use of stereotypes. “We don’t all speak this way.” “All Black people are not ghetto and ratchet”. “Why are we only portrayed like this”. I read all of the comments that I could stand, and I agreed with many of the feelings expressed by a diverse Black American community. My biggest problem with this skit was not that it relied on stereotypes, but that it propagated the idea that Black people who dip and ne ne, who go to Burger King for a piece of burger, or boldly declare that aint nobody got time for that, are not capable of having life stories that are culturally relevant and moving. Yes these stereotypes are problematic, but it is equally problematic to imply that bae can keep it on fleek, but cannot lead a life or tell a story that captivates you from beginning to end. Such an idea is an acceptable narrative, but like the young Harvard student said, “Question knowledge”. I implore you to continue questioning ideas, especially ideas about yourselves.

Two summers ago, I did one of those things that no one should ever do. I got into a great Facebook debate. The post which ‘demanded’ that I involve myself in a discussion that was never meant for me read: White gays declare in their American Apparel T-shirts We’re here we’re Queer while their Grindr profiles read: No Blacks, No femmes, No Asians. I shouted “YASS KWEEN”, louder than any non-native English speaking White Gay man, who’s twinkle toes never set foot in a Black American community! There was just one problem!. The first comment beneath this post read: Well it’s not like Black men don’t say no femmes on their Grindr posts. ‘Oh no he didin’, I thought to myself, replying why can’t we address the racism that this post is highlighting. The post itself was not about Black men on Grindr and their attitudes about Femmes. The post was about sexual racism. Here’s the deal: I’m all for talking about my community when that is the topic that is being presented, but if you only bring up topics like these when sexual racism is being brought up that let’s me know that these are not really problems that you hold close to your heart. This is an inconvenient narrative because it highlights pervasive White attitudes towards Blacks, Asians, and Femmes, and no self respecting White gay man who’s never internalised his race (his Whiteness) wants to confront the idea that his beauty and desirability reign supreme because of race/racism. This attitude reminds me of a quote from Toni Morrison. “ If I take your race away, and there you are all strung out, and all you’ve got is your little self. What is that? What are you without racism? Are you any good? Are you still strong, Are you still smart, do you still like yourself. If you can only be tall because someone else is on their knees then you have a serious problem.”

I encounter this serious problem, even though it isn’t a problem that I created. The paradigm of the inconvenient narrative shifts: acceptable narratives that uphold White supremacy encroach upon my existence, slithering into my daily life, inconveniencing me if only for a second. “Even though you’re Black you’re really beautiful. Don’t talk to me about racism. You don’t have it so bad. I’m skinny, ugly, German (and have been called a Nazi), and I’m HIV positive. Do you know where we can get some drugs. I’ve never had sex with a Black guy before.” These are vignettes of my experiences as a gay, Black, American man who has lived here in Berlin for almost nine years. I see in this community that facets of Black American culture are being appropriated. I read reviews with acceptable narratives that speak of a monolithic community of Black men who practise misogyny and homophobia across the globe and I am dubious and sometimes angry. I’m not afraid of being critiqued for being angry, because anger is not a fault. A great fault in human relations is not addressing the anger of others, and not seeing reasons why a person or a group of people are angry. This acceptable narrative that problematises Black men and Black masculinity, leaves out a violent history where Black men were torn apart from their families, forced to labour for others without benefits or compensation, enslaved, unable to freely engage in relationships, and susceptible to violence. In mainstream gay media Black men are only mentioned when it’s time to talk about STI’s, when a Transgendered member of the community has been killed by a Black male, or when homophobia is being written about in North America, or across the African continent. I remember when the Eat the poo poo video was being splashed across the interwebs, mainly by self congratulatory White Europeans. I asked myself, how did Africans view homosexuality prior to European colonisation? There isn’t a wealth of knowledge on this topic, but the information is out there and what can one discover: diverse sexual practices, intricate definitions of gender which correspond with equally complex gender roles, which were common across the continent. I would like for the Gay White community to educate themselves and to acknowledge a fact that is highly inconvenient to an ever evolving narrative of White Supremacy: The economic, scientific, religious, philosophical, and political progress that exists in so many countries that had colonies or held slaves of African descent or origin, exists because millions of Black lives were exploited. Don’t cry for me because my family is Christian and doesn’t accept my sexuality. Acknowledge that your culture’s distance from Christianity is linked with my cultures closeness to the laws and morals of this religion. I have and continue to question acceptable narratives and what I’ve realised is that the people that I have likely descended from in Africa, and at least one of the first nations that I belong to by blood, prior to colonisation had space for me, that they told acceptable narratives that were convenient to that moving space where a Black body with sexual desires like my own were told and celebrated.

Blackness to me is also faith. It is my preferred description of myself. It describes my skin colour, it describes my ethnic background(s), it describes the way that I love others, it describes my poetry, it describes my beauty, it describes my strength, and it describes my power. We define ourselves differently, and if I may I would like to quote Tricky from the song ‘Christiansand’, “You and me what does that mean. Always what does that mean? Forever, what does that mean. It means we’ll manage I’ll master your language, and in the meantime, I create my own, by my own”. I began speaking about my Grandmother as a shero, and I would like to finish with the third most heroic thing she ever did for me. Shortly before she fell ill, she said, “If you don’t start bringing girlfriends around, people are going to think you’re funny. If you are that’s okay with me. You will always have a home.” This means everything to me, not because she accepted her gay, Black, grandson, but this was a secret lesson. Home is the place where you tell stories about yourself, within yourself. It’s the best place to be, a source of refuge, with a never ending supply of nourishment. She who had repeatedly lost so much, who had been underestimated her whole life, was telling me that home was a space solely for acceptable, desirable, and honest narratives written by the movements of my experiences and my life.

Isaiah Lopaz, Him Noir