They had been following me around for at least five minutes. He was about 6’2, White, with shoulder length shaggy brown locks, wearing a maroon t-shirt, cargo shorts and flip flops. She was blonde, slightly shorter than her companion, wearing a white t-shirt, cut-off jeans, and a serene smile. All three of us were shopping at Kaiser’s, a grocery store chain, just opposite Kottbusser Tor. What do they want, I thought to myself. It was a summer’s day in July of 2007, and I had just moved to Berlin. Prior to the move Greta had drawn a map of Skalitzer str., marking three of the Ubahn stations, beginning with Schlesiches Tor. “This is where you’ll spend all of your time. You won’t need to leave this area”, she said with a smile that was saturated with memories past. “You mustn’t go to Lichtenberg. This area is a no-go for you”, Daniel chimed in with caution. The geography of the city was a mystery to me. The only visual reference, if you want to call it that, which I had for Berlin came from an episode of Alvin and the Chipmunks where our heroes dream of a Berlin where the ‘walls fall down, tumbling to the ground’. No-go areas, and living my life in the circumference of three subway stations were not tangible concepts for someone who came from a city that didn’t have a designated ‘center’. A city where cars made people feel free and not bicycles. There was, however, something that Greta and Daniel didn’t mention while telling me the best places to meet friends I had not yet made, suggesting restaurants that served delicious but suspiciously cheap meals, or highlighting clubs that I could stumble out of at sunrise. What they failed to mention, was that in Berlin people stare at you!

In trains, municipalities, and in bars who’s names I couldn’t pronounce, I found myself meeting amused, confused, and quizzical looks. Sometimes it seemed like there were people who didn’t want to see me at all. At other times people stopped me, and get this, they asked me for drugs. The first time it happened I thought, random. Then it happened a second time, and then a third time, and then it became a thing. What did this couple want? We had ended up in the same line to purchase our groceries. Blonde and Shaggy occasionally glanced at me as the conveyor belt moved our goods closer to the cashier. Just ignore them, I thought, and that’s what I did. When it was my turn to pay for the items that I had collected I didn’t even notice that the couple was waiting for me until after I had bagged my groceries. Why are they still here, and why are they looking at me. They approached me as I made my way to the exit. “You speak some German”, Shaggy probed as the Blonde’s smile melted into an analytical, lopsided curve. “Just a little ”, I replied eyeing the exit. “Me and my girlfriend, we are looking for something, you know?” “What are you looking for”, I asked naively? “You know, we are looking… for something”. Are they, like…interested in me, I thought, noticing that they were both smiling at me now. “We’re looking for something to smoke”. This again, I thought. “I don’t sell drugs”, I said, trying to mask my annoyance. Shaggy eyed me up and down his eyes wrapping their gaze around my newly grown locks. “Do you know where we can get some”? “No, I don’t. I don’t smoke. I don’t smoke weed”. This was just too much for him. His lips twisted in disbelief before parting to say, “You don’t smoke weed”? “No, I don’t”, I said moving my head left to right. “Do you know where we can dance to reggae”? “No, I don’t know. I’m not really into reggae”. In my memory he took a step backwards. Maybe two steps backward. The idea that a young Black man with newly formed locks that didn’t smoke weed or listen to reggae was not a reality, a concept, or a fact that he could compute. He was sure that I was lying to him. “Well what kind of music do you listen to”, he demanded?! “I really like Tricky and Radiohead”, I replied dryly. He looked disgusted. I didn’t sell drugs. I didn’t know where he could buy drugs. I didn’t listen to reggae music, in short, I didn’t validate any of the racial prejudices that he held so close. I did not perform his expectation of Blackness. Shaggy and the Blonde walked away. They didn’t even say goodbye. They just walked away.

The Kaiser’s calamity was an epiphany, and my ability to call this devil by it’s name based on my experiences, received inadvertent confirmations from friends and acquaintances. “It’s because you have dreadlocks”, “Lot’s of people who look like you sell drugs”, “You’re a Black guy who has dreads, of course people think you deal”, were all statements that certified what I felt in the pit of my stomach. Most of the people who authenticated this hunch were oblivious to the racist implications behind their explanations. These remarks and the messages that they contained were valid in the minds of these well educated, left leaning, free spirited individuals. Years later a friend would tell me, “You shouldn’t be mad at the people who ask you for drugs. You should be mad at the Black guys at Görlitzer park”. Görlitzer park is a place to go running, to play frisbee, to have a barbecue, but it’s also a place where you can score marijuana. There are men in every shade of brown who line one of the main entrances to the park. Some of these men will ask you if you want to buy grass. “I know this is awful, but when I go through the park, when I see what they do there, I am disgusted. This is not my culture”. That was a woman who I rented a studio apartment from which was just down the street from one of the park’s main entrances. “You’re right, that sounds awful”, I replied. Once, a very good friend of mine was carelessly questioned as to whether or not she felt ashamed when walking through Görlitzer park. She’s Black too. This is the weight of anti-Black racism. One size fits all. The only time we as Black people experience objectivity as individuals is when our words, our actions, or our beliefs denounce the impact that anti-Black racism has on our lives. That’s it!

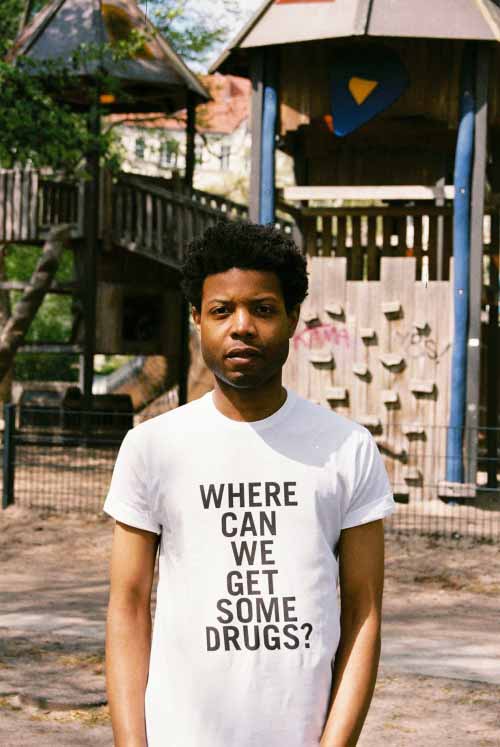

Selling marijuana isn’t a ‘bad thing’ to me, and I’m sure that it’s not such a big deal to the authorities who are aware that mostly White people are purchasing drugs from Black men at Görlitzer park. This isn’t a story about Görlitzer park though. When my locks were long enough to tie into a ponytail, I cut them. Five years and a half-fro later I’m still being asked if I sell drugs on a regular basis. When you live in a major metropolitan city for nine years and you never set eyes on a Black bank teller, a Black cashier at the grocery store, a Black postal worker, a Black public school teacher, a Black pharmacist, or a Black taxi driver, but you experience anti-Black racism because you inhabit a Black body, it’s easy to see why they think I’m a drug dealer. It’s more difficult to process how well meaning White people don’t see this as a problem. In her brilliant Ted Talk The Danger Of The Single Story which I watch often, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie states that the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue but that they are incomplete. It’s difficult to disagree with this, but when I find myself meandering on the power of stereotypes, something else comes to mind. If one stereotype is valid, aren’t all stereotypes in effect valid? The same person who expects me to be a dynamic dancer with preternatural rhythm might be the same person who holds their belongings just a little bit closer when I walk by. The same person who chats me up at a bar because he thinks that I must be wild in bed, might be the same person who glosses over my CV because it is evident that the experiences listed there are the experiences of a Black person. I laugh when we try to drum up stereotypes meant to frame Whiteness in order to illustrate how racial prejudice operates and impacts our lives. I laugh, but I know that these examples fail. They fail because White people don’t know what it’s like to be racially oppressed. There’s a quote that I’ve archived somewhere on the interwebs. It says something to the effect of: Black people know what it’s like to experience anti-Black racism. It’s White people who need convincing that racism exists. With this in mind my default answer for “Do you know where we can get some drugs” is not really an answer, but a question of my own. “Do I look like I sell or use drugs”, I ask? It’s a question that if answered honestly, demonstrates the implicit racial bias that the enquirer nourishes without question, without critique, without a doubt.

Isaiah Lopaz, Him Noir.

Have you found yourself in the position of constantly being asked if you sell drugs while minding your business living your life? If the answer is yes, I’d like to hear about it. Message me at therealhimnoir@gmail.com